“Primitive therapsids are present as fossils in certain Middle Permian deposits; later forms are known from every continent except Australia but are commonest in the Late Permian and Early Triassic of South Africa.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2024

I made a special trip last Saturday to the Iziko Natural History Museum in Cape Town on the quest for dinosaurs and therapsids. I hadn’t been there for some years – maybe ten in fact - and all my trips have been great experiences – I remember having a great time interviewing Dr Peter Best, the whale expert for my book on the Whale Trail of South Africa. By the way, they have a great whale exhibit, with a blue whale skeleton suspended from the roof in the Whale Well. But this trip was to grab some pics of two wonderful African dinosaurs from Niger, and explore the fossils from the Karoo Basin.

The Karoo, an almost mythical, semi-desert region that makes up the central part of South Africa, is known for its beautiful landscapes, traditional wind pumps, whitewashed farmhouses and millions of sheep which taste like no other thanks to the herbaceous vegetation on which they browse. This semi-desert region of South Africa is famous for its stark beauty, and for those in the know, its fossils.

Earth’s ancient history is written in these rocks that stretch back hundreds of millions of years. These sediments preserve a wealth of fossils that showcase the remarkable evolution of life on Earth. Among these fossils are the remains of therapsids, often incorrectly called “mammal-like reptiles,” which document the slow but steady evolutionary transition from reptiles to the first mammals.

The Karoo Basin is a nearly uninterrupted record

The sediments of the Karoo Supergroup, as it is known, comprises a sequence of rocks that hold nearly 120 million years of Earth’s history, spanning from about 300 to 180 million years ago. During this period, South Africa was part of Gondwana, a massive ancient continent that included most of today’s southern hemisphere continents. The sediments of the Karoo Basin are a nearly uninterrupted record of climate change and life on land, offering scientists invaluable insights into our understanding of how ancient ecosystems responded to environmental changes over incredibly long time frames.

The Formation of the Karoo Supergroup

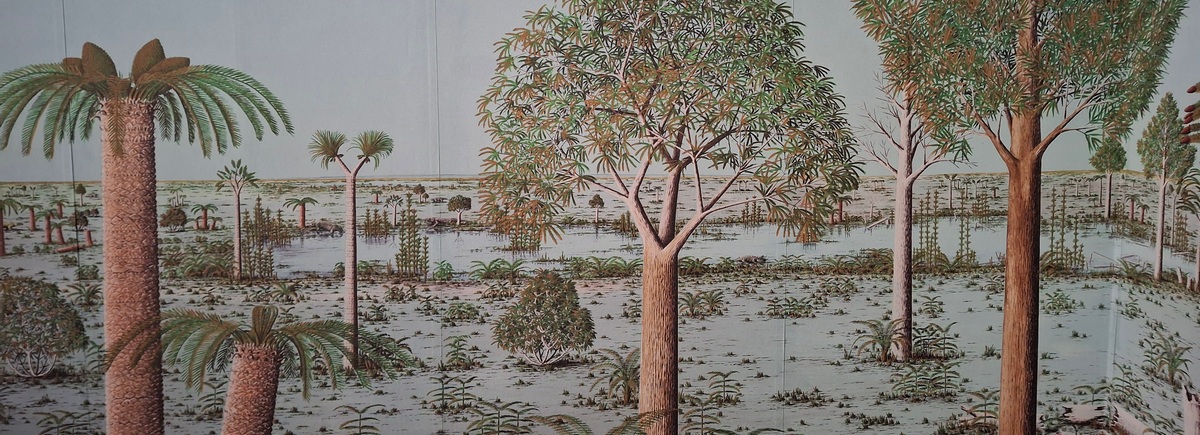

The Karoo Basin’s sediments accumulated over millions of years through geological processes. Initially starting out as an inland sea, fringed by coal swamps in the north and north east and mountains to the south, the basin slowly filled with sediment as rivers deposited their sedimentary load into the basin. Eventually the sea became choked with mud, silt and sand, turning into a vast plain characterised by meandering rivers and lakes, and populated by some very strange creatures that we shall look at shortly. These sediments slowly hardened into rock, preserving the remains of plants and animals that lived there. Over time, the sediments of the Karoo basin stacked up to form a natural history book with pages that span the Late Palaeozoic to the Early Mesozoic Eras.

What makes the Karoo Supergroup so unique is that its layers were deposited almost continuously. This nearly complete record of life on land is rare in the fossil world, where much of the Earth’s history is fragmented due to erosion and other geological disruptions. Because of this uninterrupted sequence, the Karoo rocks can tell us a great deal about how life on Earth was impacted by major changes in climate and habitat. The result is an invaluable archive, giving researchers clues to how terrestrial life evolved over an immense span of time.

Discovering Therapsids: The "Mammal-Like Reptiles"

One of the most important groups of fossils found in the Karoo is the therapsids, a group of ancient vertebrates that thrived between roughly 270 and 200 million years ago. Therapsids are crucial in the story of life on Earth because they represent an evolutionary bridge between reptiles and mammals. Though they are often nicknamed “mammal-like reptiles,” therapsids aren’t true reptiles; they belong to a separate group of animals called synapsids, which includes all mammals.

Therapsids came in a wide variety of forms. Some were massive, plant-eating animals with thick skulls, like the Dinocephalians, while others, such as Gorgonopsians, were fearsome, sabre-toothed predators. The Karoo’s diversity of therapsid fossils shows just how adaptable these animals were, filling different roles in the ecosystem much like mammals do today. Some therapsids were specialized for hunting, while others evolved to feed on plants, developing robust body structures to support their size and unique feeding habits.

As evolutionary pioneers, therapsids began to develop features we now associate with mammals, like a more upright posture and stronger jaws. By studying the bones of these creatures, palaeontologists can trace how early synapsids slowly transformed over millions of years, developing characteristics that would later define mammals. This step-by-step evolutionary journey is vividly documented in the Karoo fossils, giving us a window into how our earliest ancestors evolved.

The Great Permian-Triassic Extinction: A Turning Point for Therapsids

Around 252 million years ago, Earth experienced the most severe extinction event in its history—the Permian-Triassic extinction, sometimes called “The Great Dying.” This extinction event wiped out approximately 90% of all marine life and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates, reshaping the planet’s ecosystems. Massive volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia are thought to have caused extreme climate change, including a rise in global temperatures and a depletion of oxygen in the oceans.

The Therapsids, despite being severely impacted by this extinction, had certain members that survived, including a group called cynodonts. Cynodonts are particularly important because they eventually gave rise to the first true mammals. These small, adaptable animals had several features that may have helped them survive through harsh climates and environmental changes, such as burrowing behaviour and possibly even warm-bloodedness. Burrowing would have helped them escape the extreme heat and protect themselves from the unstable atmosphere that resulted from the environmental pressures that drove 95 percent of all life to extinction.

In the aftermath of the extinction, cynodonts diversified and evolved new traits, setting the stage for the rise of mammals. The survival and adaptability of cynodonts highlight the resilience of therapsids and their ability to weather dramatic changes in their environment.

How Cynodonts Bridged the Gap to Mammals

Cynodonts were a specialized branch of therapsids and are perhaps the most crucial group in the evolution of mammals. Unlike their earlier relatives, they exhibited a range of features that we now associate with modern mammals. Cynodonts had differentiated teeth, with different types for biting, slicing, and chewing. This allowed them to eat a varied diet, which could have included plants, insects, and small animals, depending on the species.

Another significant adaptation was the development of a secondary palate, which allowed them to breathe while chewing—an essential feature for mammals. Fossils suggest they may have had fur or whiskers, possibly as an adaptation for insulation. In addition, some cynodonts had a more advanced respiratory system that might have included a diaphragm, the muscle that helps mammals breathe more efficiently. These adaptations not only set the foundation for mammals but also enabled cynodonts to thrive in a range of habitats.

By the late Triassic period, some cynodonts had become small, nocturnal animals, which may have helped them avoid the larger predators of the time, like early dinosaurs. This “hidden” lifestyle allowed cynodonts to survive alongside these dominant reptiles and to continue evolving in new directions.

Other Fossil Treasures in the Karoo

The Karoo is home to more than just therapsid fossils. Fossils found within the Karoo Supergroup include ancient plants, from large plant fossils to microscopic pollen and spores that tell us about the vegetation of the time. Fossils of rare insects and fish offer clues to other elements of the Karoo ecosystem. There are also fossils of other important vertebrates, like amphibians called temnospondyls and early reptiles, including the ancestors of crocodiles and dinosaurs.

The Karoo rocks also preserve trace fossils, such as burrows, coprolites (fossilised droppings), and trackways. These traces give additional clues about the behaviour and lifestyles of the animals that once lived here. For example, burrows suggest that some animals may have avoided harsh weather or predators by going underground, while trackways reveal details about how these animals moved and interacted with their environment.

The Karoo Today: A Natural and Scientific Treasure

The Karoo Basin is considered a national treasure, not only for its abundance of fossils but also for its unique modern ecosystem. Today, the Karoo is a vast semi-desert, home to specialized desert plants like succulents and unique wildlife adapted to its dry climate. This fascinating landscape draws scientists, naturalists, and tourists alike, all captivated by the stark beauty and ancient history preserved in its rocks.

So if you are in Cape Town, go to the Iziko Museum and check out some of these very strange fossils that have been unearthed in the Karoo. Researchers come from around the world to study these collections, and so you could be rubbing shoulders with some famous palaeontologists when you make your visit. Certainly you will be checking out the bones of your ancestors, albeit distant ones, because, like you, they are all synapsids.