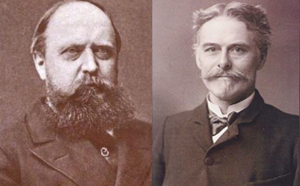

The Bone Wars, waged by Edward Drinker Cope (right) and Othniel Charles Marsh (left) between 1877 and 1892, were both a high and low point in the science of palaeontology. Between the two of them they collected and classified 142 new species of dinosaurs, mostly from the fantastically rich bone beds of the Morrison Formation, although today only 32 of those species are valid. From initial friendship to outright war, they battled it out in the newspapers, the scientific journals and in the wild badlands of Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming. And who won? Read on to find out more.

The Bone Wars were fought out by Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh from 1877 to 1892. At the end of the war they had disgraced themselves but by competing with each other they had discovered over a hundred new species of dinosaur.

The Bone Wars were both a high and low point in the science of palaeontology. Between the two of them they collected and classified 142 new species of dinosaurs, mostly from the fantastically rich bone beds of the Morrison Formation, although today only 32 of those species are valid. From initial friendship to outright war, they battled it out in the newspapers, the scientific journals and in the wild badlands of Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming.

Bribery, theft, dynamite and stone throwing

OC Marsh was head of the Palaeontology Department of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale, and Edward Drinker Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Weapons of war included bribery, theft, dynamite, stone throwing, spying and attacks in the scientific publications in an attempt to destroy each other’s reputation. They didn’t seem to care about the money, and in fact Cope almost bankrupted himself financing fossil hunting expeditions.

They disgraced themselves

In trying to disgrace each other they disgraced themselves. Other famous palaeontologists of the time refused to be drawn into the war and left the battle to Cope and Marsh. And yet, and yet, in spite of all the skulduggery and madness they left behind a legacy which lives on to this day. Some of the most famous dinosaurs were found by these two men in their quest for the top palaeontological spot, driven by their intense rivalry and hatred for each other.

I have to wonder what they could have achieved if they had combined their skills and resources. Perhaps that hatred was the catalyst that drove them to achieve what they did, and without it the outcomes would have been very different.

Sparked the public's interest

However, from our point of view, it sparked the public’s interest in dinosaurs and prehistoric life which has not died away since those mad days back in the late 1800’s. And which got us all interested in dinosaurs - some of us even crazy about them.

They both liked a good fight

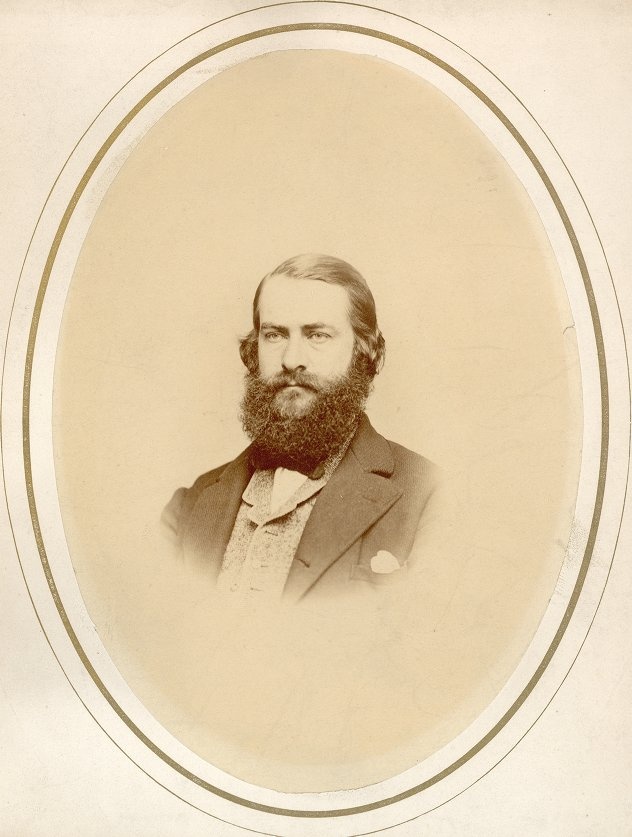

Cope and Marsh met in Berlin in 1864 and initially were friends, hanging out together for several days and in the first great palaeontological love-in, named dinosaurs after each other. Both were larger than life characters with strong personalities, liked a good fight, and both distrusted everybody. Cope came from a wealthy family with good family ties, which allowed him to study to become a naturalist and ultimately professor of zoology at Haverford College.

Marsh came from a poor background but his uncle, George Peabody had pots of money and so Marsh managed to get Uncle George to stump up the money to build the Peabody Museum of Natural History, with himself as the head of the museum. No surprises there. Perhaps Cope was a bit of a snob, looking down his nose at Marsh's humble background.

Marsh did a dirty deed

It all started to go wrong when Cope took Marsh to a marl pit in New Jersey to show him Hadrosaur bones. This was one of the first dinosaur finds in America and little did they realise, or anybody else, how it was all going to end. They parted on friendly terms but then Marsh did a dirty deed, going back to the quarry and paying the pit operators to send all future finds to him, instead of Cope.

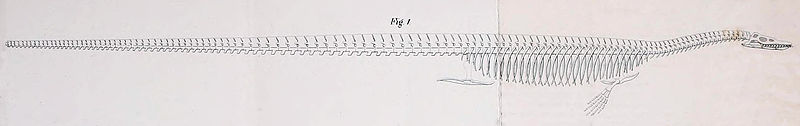

This was a very underhand thing of Marsh to do and Cope's reaction to it is understandable. Things went rapidly downhill from then on and the two began attacking each other in the scientific publications. One of the opening salvos of this war was when Cope was publicly humiliated by Marsh who pointed out that he (Cope) had put the head of a plesiosaur, Elasmosaurus, onto its tail.

Back in the 1870’s word came out of the American West that large fossils were being dug up. This of course attracted the attention of our two bone hunters and Cope managed to get himself a position at the US Geological Survey, which allowed him to officially go fossil hunting. June 1872 found Cope on his first trip to the Eocene bone beds of Wyoming. The famous American naturalist of the time, Joseph Leidy, was angered by this as he considered this to be his turf, so he formally made a complaint to the head of the Geological Survey, Hayden. As a result, Leidy and Hayden fell out with each other and needless to say, Leidy fell out with Cope.

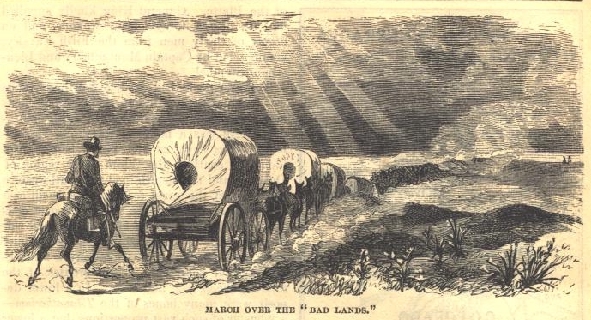

Back then, bringing fossils back east was quite an undertaking, and remember that roads were rudimentary and there were no trucks, cranes, forklifts or telephones to assist. It was all muscle power and animal drawn carts. Cope, thanks to his position in the Geological Survey, was relying on assistance from his employees but this failed to turn up, so he had to organise his own crew to get the bones home. Turns out that two of his new employees actually worked for Marsh! And so the plot thickens.

However, the great irony was that Marsh didn’t know that his employees were working for Cope, so he was outraged when he heard the news that his employees were also working for his rival. Clearly those men were scallywags and were happy to collect two salaries. They spun Marsh a story that they had taken the job with Cope to lead him away from the best fossils.

Their relationship went downhill

Cope met with success on his expedition, crossing some wild country where he found dozens of new species. Meanwhile, one of Marsh's men accidentally forwarded some of his material to Cope, who sent them back to Marsh, but that was the end of pleasantries and their relationship went downhill soon after.

By the spring of 1872 it was open war. Leidy, Cope and Marsh were digging up bones at a furious rate, shipping them home, and constantly announcing new species. Problem was, they were all digging up the same species and naming them, with little regard to the fact that some of these species had already been classified. The rule is that the scientist who first discovers a species gets to name it, and so the war continued in the scientific journals. Marsh won this battle of the larger war, as more of his names were valid than Copes.

The pile of bones grew higher

While the scientists fought it out in the publications, they continued their fossil hunting out west, with Marsh making his last Yale-financed trip in 1873 with a group of students and soldiers who came along as a show of force. After that Marsh stayed at home and paid local collectors to do the hard digging for him. The pile of bones grew ever higher and he was running a backlog in terms of getting through the scientific descriptions of his collection of fossils.

That didn’t stop him collecting though – his appetite for those bones never went away. Cope too was collecting, and brought home more fossils than he had in the previous year. Marsh had more feet on the ground though and Cope had to work around Marsh’s men who were understandably unwelcoming of him and his team. Cope also left the Geological Survey and found a job with the Army Corp of Engineers which forced him to tag along on their surveys rather than dig where he wanted.

Gold was Discovered in the Black Hills

Dakota, 1875. Gold is discovered in the Black Hills which led to tensions between the Native Americans and the US. This was inconvenient for Marsh as those bone beds lay right where those tensions were being played out. So, Marsh became a politician and a businessman, agreeing to pay Chief Red Cloud of the Sioux for any bones that he dug up. He also promised to lobby for the Sioux in Washington against their ill treatment which he did in fact do.

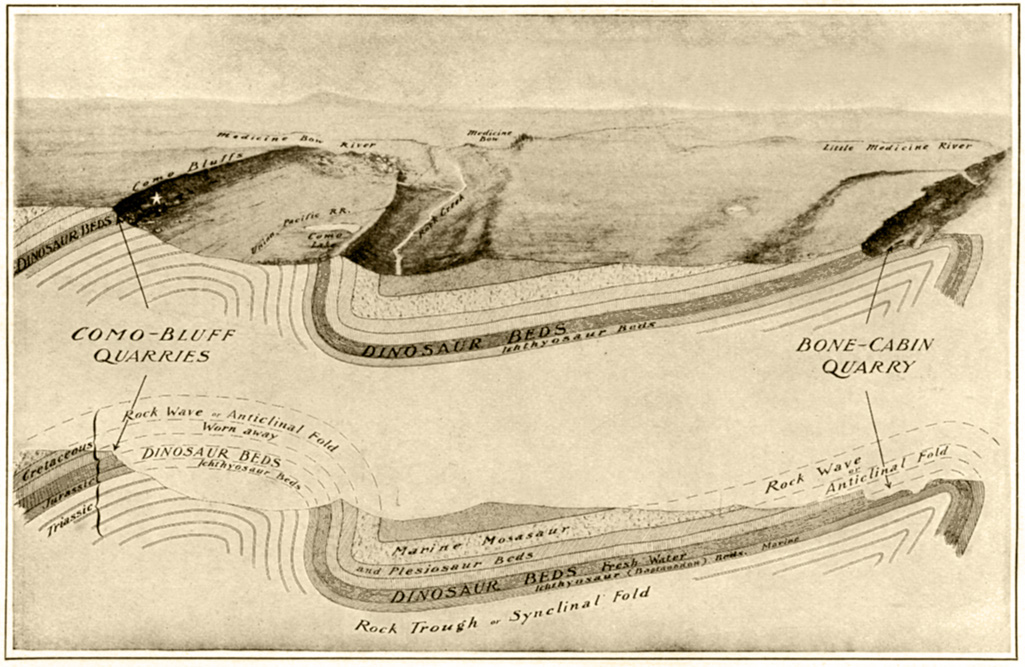

Como Bluff is arguably the sacred ground of palaeontology. Mention the words Morrison Formation to palaeontologists and their eyes light up. Why? Because it was one of the most prolific bone beds in the history of vertebrate palaeontology. Back in 1877 a geologist called Arthur Lakes wrote to Marsh saying that he had found massive bones sticking out of the rock when on a hike near the town of Morrison. In his letter he correctly deduced that they were “a vertebra and a humerus of some gigantic saurian.” He then dug up some bones and sent them to New Haven and also a shipment to Cope.

Ouch for Cope

It makes me think that Cope and Marsh were quite famous at the time as people seemed to find little difficulty in knowing where to send letters and bones. Marsh took his time in responding to Lakes, but sent $100 to keep his find a secret. But it was too late - the cat was out of the bag - so Marsh sent his field collector Mudge to Morrison to secure the spot and get Lakes onto his payroll. Marsh’s quick work after a slow start secured Lake’s services, who wrote to Cope saying that all the bones would in future be shipped to Marsh. Ouch for Cope!

But life has its funny twists and turns. Cope received a letter from a Mr OW Lucas, a naturalist who had been collecting plants near Canon City, Colorado. Guess what was in that letter? No prizes for that one – he had found a pile of old bones. Some samples then arrived and Cope concluded that they were the bones of large herbivores.

Williston was nearly killed

Marsh, never one to miss a trick, then sent Mudge and his student assistant Williston to steal the find by setting up a bone quarry near Canon. However, Lucas refused to work for Marsh and nailed his banner to Cope’s mast. Back to Morrison went Williston who was nearly killed when his bone quarry collapsed. This would have been the end of Marsh’s supply of bones but then a third letter arrived to save the day.

At the time they were building the Transcontinental Railway through the wild lands of Wyoming. The letter was signed by Harlow and Edwards, whose real names were actually Carlin and Reed, and claimed that they had found plenty of fossils in Como Bluff. Williston, that willing but tired workhorse of Marsh’s, was sent back to Como Bluff to find out what was going ton. He confirmed that indeed there were plenty of bones in the bluff.

Bone collecting was more fun

Money was sent to Harlow and Edwards (aka Carlin and Reed - I am not sure what to call them) to keep them bone hunting. They had a problem cashing the cheques as Marsh had made them out to Harlow and Edwards and not their real names, so there is a lesson in that. I can imagine the arguments in the bank and the letters going back and forth to solve that little problem. They eventually went to meet Marsh personally and managed to get contracts drawn up for ongoing bone collecting. Seems like bone collecting was more fun, and better paid than working on the railway.

However, they weren’t too happy about the agreed terms so once again trouble was brewing in the Bone Wars. However, Como Bluff and surrounds began to produce some amazing fossils and he received shed loads of bones via the new railway throughout 1877. This is when some of those famous dinosaurs which we all love were first described – names like Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, and Apatosaurus.

No honest or honourable men

It seems that there were no honest or honourable men in those crazy days. Perhaps they were just falling into line with their respective bosses. Word of the discovery spread, and Carlin and Reed spread rumours around and informed the press of their finds. An article in the Laramie Daily Sentinel informed the world of the discoveries, and inflated the prices being paid for the bones. Usual story that one – prospectors had been doing that for years – exaggerating the richness and value of mineral deposits.

Cope sent dinosaur rustlers to steal fossils

Not to be squeezed out of the bone Bonanza, Cope sent dinosaur rustlers out to Como to steal fossils from Marsh. I guess when you have to employ scallywags to do your dirty work for you, you can’t always rely on their honesty and loyalty. Carlin also became fed up with Marsh’s slow payments and went to work for Cope. Reed stayed on with Marsh. For fifteen years both sides battled the weather and each other. They sabotaged the digs, they obstructed each other. Reed and Carlin fell out with one another too, not surprisingly as they were now in enemy camps. Once Carlin managed to lock Reed out of the Como train station which forced Reed to crate bones in bitterly cold winter weather. Under Cope's direction, Carlin opened up his own bone quarry in Como Bluff with Reed spying on his former colleague under Marsh’s orders.

Things got worse

Marsh’s quarries began to run out of bones and so Reed destroyed the remaining bones rather than have them fall into the hands of Cope. Typical tactics of war, destroying things to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. Lakes, whom we met earlier from Canon, was sent by Marsh to assist with the excavations with Marsh also paying his quarries a visit. More quarries were opened up but by this time Lakes and Carlin were not talking and both resigned. Things got worse as new recruits fell out with each other and that old stalwart of Marsh’s, Williston, resigning and going to work for Cope! How the world had changed.

Other parties began to come out west to hunt for bones, including Professor Alexander Agassiz of Harvard, so competition was on the increase. In good American business tradition Carlin and Williston founded a bone company to sell fossils to the highest bidder. Reed left his bone digging career and became a shepherd - clearly a less stressful job - and Marsh's Como quarries yielded little after his departure.

Marsh was winning

However, Marsh was winning the quarry battle, with more operational quarries than Cope. Cope at the time was drowning in fossils back east but was technically losing the bone wars. The two men continued to fight it out, accusing each other of spying, stealing and bribery. On one occasion their teams threw rocks at each other. It does all seem quite laughable now, but tensions were clearly running high out there on the bone-strewn battle fields.

Remove his error from the public record

They say the pen is mightier than the sword and it was in the scientific journals that the war really took place. Marsh and Cope battled it out in the journals while their men fought it out in the west. Remember Cope's mistake about putting the head of Elasmosaurus on its tail? Well, he tried to buy up every copy of that journal to remove his error from the public record. Leidy had made the same error too, so it wasn’t just Cope who got things wrong.

Marsh put the wrong skull on Apatosaurus

Cope produced piles of scientific papers – far more than Marsh – and Marsh took pleasure sniping from the side-lines whenever he found an error in Cope’s work. Marsh wasn't totally immune from making mistakes either, erroneously put the wrong skull on Apatosaurus and declaring a new genus Brontosaurus. Strangely enough that so called misclassification has been revised in the last couple of years.

However, people began to tire of this mad battle and by the late 1880s most of the interest in the fight had blown over. Marsh landed himself a position as head of the Geological Survey's consolidated government while Cope struggled to pay his bills. Marsh was well connected and used his contacts to block Cope from getting work in various universities and government departments.

Marsh remained a bad payer

Cope struggled financially and invested in silver mines, which initially did well until the bottom fell out of the silver market. Marsh as always remained a bad payer and gave little credit to his loyal workers for the finds and scientific contributions which they had made, and so eventually Williston and others moved on to greener pastures.

The battle was taken to the newspapers

Cope befriended Henry Fairfield Osborn, who was Professor of Anatomy at Princeton and very influential. There had been some shenanigans within the geological survey with Marsh and Powell, who was the head of the unit, being implicated. Cope went to the papers with a journal in which he had kept a record of Marsh’s and Powell’s wheelings and dealings in the Geological Survey. And so the battle was taken to the newspapers, with accusations and counter accusations being levelled at each other, and at the end of it both palaeontologist's reputations were in tatters.

The Public got fed up with their behaviour

Other palaeontologists were fed up with the behaviour of these two men and were equally fed up to see their names in dragged into print by both Marsh and Cope. At the end no one was the winner. Eventually Powell had to answer to his bosses as to where the monies had gone and as a result demanded Marsh’s resignation, and severed ties with him. Marsh’s influence began to wane as some of his old cronies retired or passed away.

Cope had by this stage landed a job at the University of Pennsylvania which helped him get his finances back on an even keel. He then went on to work for the Texas Geological Survey and eventually got Leidy’s old job as Professor of Zoology. He was then elected President of the National Association for the Advancement of Science, just as Marsh stepped down as head of the Academy of Sciences.

In the end, Marsh had discovered 80 new dinosaurs and Cope 56

At the end of the day, Marsh had discovered 80 new dinosaurs and Cope 56. If we only look at it in those terms then Marsh ‘won’ the war. It ultimately boiled down to money – and Marsh had more of it than Cope. Cope however, was more the academic, with a wider range of palaeontological interests, while Marsh just chased down reptiles and mammals.

Driven the science to new heights

Once the dust had settled, some of the most well-known dinosaurs, including species of Triceratops, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Camarasaurus and Coelophysis had been described. They had driven the new science of palaeontology to new heights, particularly in view of the fact that only nine dinosaurs had been discovered before the Bone Wars.

All the twists and turns of this sorry saga are quite hard to follow, which is what happens in times of war, so well done on reading to the end - you would be a good palaeontologist as it takes staying power to find and dig up bones.

Birds are descended from dinosaurs

Marsh supported the idea that birds were descended from dinosaurs and this theory is still upheld by the scientific community today. Other theories went into the rubbish bin. The public were fascinated by the discoveries and the dinosaur exhibits that popped up in the museums – a fascination that has yet to go extinct.

As palaeontologist Robert Bakker stated, "The dinosaurs that came from Como Bluff not only filled museums, they filled magazine articles, textbooks, they filled people's minds."

And seeing that you are here, grab yourself a copy of our free colouring book, which is full of wonderful dinosaurs and other Mesozoic creatures for you to bring back to life.